Delivery riders connected to platform Glovo do not all get employment contracts, but are covered by the ‘Couriers Pledge’ in 21 countries. With this, the company promises delivery workers safety, community, equality and a fair income. Why, how does it work and what does a platform worker get out of it? Martijn Arets travelled to Barcelona and spoke to Glovo spokesperson Magalí Gurman.

The main discussion about delivery via platforms is about whether such a platform should employ the couriers. After all, in many Western countries, things like safety and fair pay are linked to an employment contract. But this is far from common everywhere. Therefore, platforms are looking for ways to offer riders better conditions regardless of their employment status. One such platform company is Glovo. For The Gig Work Podcast from the WageIndicator Foundation, I travelled to Barcelona and sat down with Magalí Gurman, Institutional affairs & government relations at Glovo.

From customer to courier: keeping everyone happy

The creators of delivery service Glovo know all too well how important international differences are. The Spanish company operates in 24 countries in Southern Europe, Eastern Asia and Africa, among others. Through the Glovo app, delivery drivers bring all kinds of products to private customers: from meals to flowers and groceries. Customers order something from a restaurant or retailer via the Glovo app, the delivery drivers pick it up and bring it to the customer as soon as possible.

“So basically we have three sorts of clients: customers, retailers and delivery drivers,” Gurman says. “Each has its own app with corresponding processes, because we are providing a different service for each user.”

Local differences

In addition, operational needs differ by region, she explains. “For example, here in Barcelona it is normal for delivery drivers to ride bikes or scooters. In cold Romania, on the contrary, most couriers deliver by car. What we also see is that delivery times changes from city to city because of different reasons, like the state of the streets, and therefore, people are used to different types of services. Moreover, laws and regulations vary from country to country.”

It is up to Glovo to meet all these needs and preferences, she says. “Our goal is for all users to be satisfied, not just the end customers.”

‘Flexibility does not exclude good working conditions’

To better meet the needs of couriers, Glovo introduced a ‘Couriers Pledge’ in 2021. With this, the company aims to improve the conditions for all couriers, regardless of their working status. “Two years ago, there was much less regulation around platform workers than now,” she says. “We wanted to lead the way and show that the flexibility of the platform economy does not preclude good working conditions.”

Because there are big international differences in legislation and preferences, Glovo introduces the Pledge on a country-by-country basis each time. This starts with research into local laws and regulations and an exploration of the possibilities within the organisation. How much money and people does the platform have available in this region? Meanwhile, 21 of the 24 countries each have their own Pledge.

“With this, we want to set a standard example for the platform economy sector,” says Gurman.

Safety, community, equality and income

The Pledge rests on four pillars: safety, community, equality and fair earnings. Once a rider has delivered a certain number of products within a certain period of time, they can access these benefits. For example, couriers get safety training, helmets and parental leave. The exact conditions vary from country to country and depend on the couriers’ preferences, among other things.

Under the ‘community’ pillar, Glovo organises events to connect couriers with each other. “Sometimes we discover needs we could never have thought of ourselves. For instance, it turned out that relatively many couriers in Kenya had eye problems. We work with a company that does eye checks and we reimburse glasses if needed.”

The current Pledge is the foundation, says Gurman. “We want to be more and more responsive to what couriers need to deliver in a healthy and safe way. Satisfied couriers are also good for business. That’s why we keep researching, talking and adapting.”

Independent help

Glovo also works with two independent organisations around fair working conditions and pay for platform workers: Fairwork and the WageIndicator Foundation. “Organisations like these keep us on our toes,” says Gurman. “An organisation like Fairwork critically assesses our practices and sets our conditions against those of other platforms. This is how Fairwork helps us improve operations. Our working conditions in Africa are currently the best rated in that region.”

WageIndicator Foundation helps Glovo with the third pillar of the Pledge: payment. “This is the most important issue for couriers and at the same time the most complicated,” says Gurman. “WageIndicator helps us with data on living wages and minimum wages for comparable work. Rates vary from country to country and are constantly changing.”

Most Glovo couriers work as freelancers. Political parties and trade unions in several countries advocate giving these workers employment contracts. “An employment contract does not necessarily lead to better working conditions,” says Gurman. “What an employment contract means for working conditions varies greatly from country to country. The Pledge applies to every courier, regardless of the form of contract.”

Labour contract is not always an improvement

Gurman is right: a labour contract is by no means always better for a courier. For example, if delivery workers are employed through a middleman, they often get the most minimal protection legally possible.

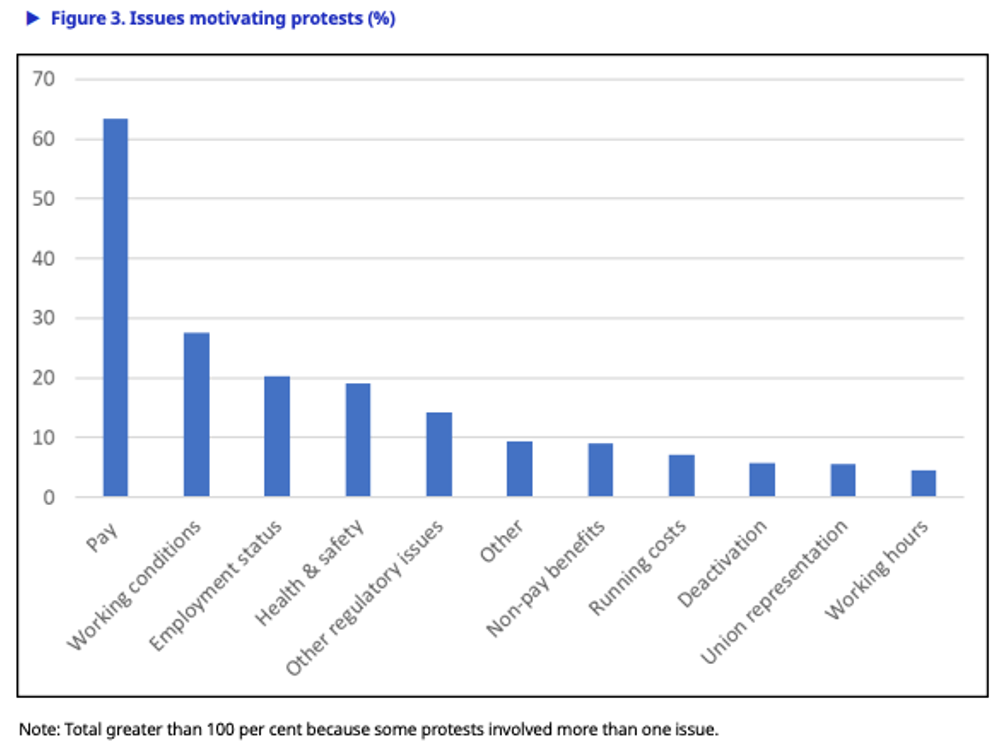

Moreover, it is not always what working people want, figures from the Leeds Index of Platform Labour Protest show. In only 20% of all demonstrations do workers ask for a labour contract, analysis of nearly 2,000 protests shows. This varies greatly by country. For instance, ‘employment status’ is an issue in 37.1% of protests in North America, because it brings more security there. In Africa, it was an issue in only 4.7% of protests, because a contract offers hardly any benefits there.

Analysis

I like how Glovo is trying to improve conditions for couriers. Especially when you know that working as a delivery driver is done in an informal way in many countries. So before, couriers had no protection at all.

For Glovo, it is a balancing act between what is allowed and what is possible, including financially. And it is true that an employment contract is not worth the same everywhere, but in certain (European) countries it does offer more protection. Could the Pledge be an addition there? There are also several important employment conditions not included in the Pledge. Consider transparency, explainability and accountability of automatic decision-making processes and worker representation. According to Gurman, this is now “not always legally possible”, but that is a little too easily dismissed. In my opinion, there is quite a solution to this. Where there is a will, there is a way.

So the Pledge is not yet perfect, but it is a good step in the right direction and a great example of how to take into account different wishes and circumstances in various countries in which a platform operates.